Integer factorization

| Can integer factorization be done in polynomial time? |

In number theory, integer factorization or prime factorization is the decomposition of a composite number into smaller non-trivial divisors, which when multiplied together equal the original integer.

When the numbers are very large, no efficient, non-quantum integer factorization algorithm is known; an effort concluded in 2009 by several researchers factored a 232-digit number (RSA-768), utilizing hundreds of machines over a span of 2 years.[1] The presumed difficulty of this problem is at the heart of certain algorithms in cryptography such as RSA. Many areas of mathematics and computer science have been brought to bear on the problem, including elliptic curves, algebraic number theory, and quantum computing.

Not all numbers of a given length are equally hard to factor. The hardest instances of these problems (for currently known techniques) are semiprimes, the product of two prime numbers. When they are both large, randomly chosen, and about the same size (but not too close, e.g. to avoid efficient factorization by Fermat's factorization method), even the fastest prime factorization algorithms on the fastest computers can take enough time to make the search impractical.

Many cryptographic protocols are based on the difficulty of factoring large composite integers or a related problem, the RSA problem. An algorithm that efficiently factors an arbitrary integer would render RSA-based public-key cryptography insecure.

Contents |

Prime decomposition

By the fundamental theorem of arithmetic, every positive integer has a unique prime factorization. (A special case for 1 is not needed using an appropriate notion of the empty product.) However, the fundamental theorem of arithmetic gives no insight into how to obtain an integer's prime factorization; it only guarantees its existence.

Given a general algorithm for integer factorization, one can factor any integer down to its constituent prime factors by repeated application of this algorithm. However, this is not the case with a special-purpose factorization algorithm, since it may not apply to the smaller factors that occur during decomposition, or may execute very slowly on these values. For example, trial division will quickly factor 2 × (2521 − 1) × (2607 − 1), but will not quickly factor the resulting factors.

Current state of the art

The most difficult integers to factor in practice using existing algorithms are those that are products of two large primes of similar size, and for this reason these are the integers used in cryptographic applications. The largest such semiprime yet factored was RSA-768, a 768-bit number with 232 decimal digits, on December 12, 2009.[1] This factorization was a collaboration of several research institutions, spanning two years and taking the equivalent of almost 2000 years of computing on a single core 2.2 GHz AMD Opteron. Like all recent factorization records, this factorization was completed with a highly-optimized implementation of the general number field sieve run on hundreds of machines.

Difficulty and complexity

If a large, b-bit number is the product of two primes that are roughly the same size, then no algorithm has been published that can factor in polynomial time, i.e., that can factor it in time O(bk) for some constant k. There are published algorithms that are faster than O((1+ε)b) for all positive ε, i.e., sub-exponential.

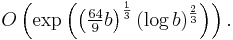

The best published asymptotic running time is for the general number field sieve (GNFS) algorithm, which, for a b-bit number n, is:

For an ordinary computer, GNFS is the best published algorithm for large n (more than about 100 digits). For a quantum computer, however, Peter Shor discovered an algorithm in 1994 that solves it in polynomial time. This will have significant implications for cryptography if a large quantum computer is ever built. Shor's algorithm takes only O(b3) time and O(b) space on b-bit number inputs. In 2001, the first 7-qubit quantum computer became the first to run Shor's algorithm. It factored the number 15.[2]

When discussing what complexity classes the integer factorization problem falls into, it's necessary to distinguish two slightly different versions of the problem:

- The function problem version: given an integer N, find an integer d with 1 < d < N that divides N (or conclude that N is prime). This problem is trivially in FNP and it's not known whether it lies in FP or not. This is the version solved by most practical implementations.

- The decision problem version: given an integer N and an integer M with 1 ≤ M ≤ N, does N have a factor d with 1 < d < M? This version is useful because most well-studied complexity classes are defined as classes of decision problems, not function problems. This is a natural decision version of the problem, analogous to those frequently used for optimization problems, because it can be combined with binary search to solve the function problem version in a logarithmic number of queries.

It is not known exactly which complexity classes contain the decision version of the integer factorization problem. It is known to be in both NP and co-NP. This is because both YES and NO answers can be verified in polynomial time given the prime factors (we can verify their primality using the AKS primality test, and that their product is N by multiplication). The fundamental theorem of arithmetic guarantees that there is only one possible string that will be accepted (providing the factors are required to be listed in order), which shows that the problem is in both UP and co-UP.[3] It is known to be in BQP because of Shor's algorithm. It is suspected to be outside of all three of the complexity classes P, NP-complete, and co-NP-complete. It is therefore a candidate for the NP-intermediate complexity class. If it could be proved that it is in either NP-Complete or co-NP-Complete, that would imply NP = co-NP. That would be a very surprising result, and therefore integer factorization is widely suspected to be outside both of those classes. Many people have tried to find classical polynomial-time algorithms for it and failed, and therefore it is widely suspected to be outside P.

In contrast, the decision problem "is N a composite number?" (or equivalently: "is N a prime number?") appears to be much easier than the problem of actually finding the factors of N. Specifically, the former can be solved in polynomial time (in the number n of digits of N) with the AKS primality test. In addition, there are a number of probabilistic algorithms that can test primality very quickly in practice if one is willing to accept the vanishingly small possibility of error. The ease of primality testing is a crucial part of the RSA algorithm, as it is necessary to find large prime numbers to start with.

Factoring algorithms

Special-purpose

A special-purpose factoring algorithm's running time depends on the properties of the number to be factored or on one of its unknown factors: size, special form, etc. Exactly what the running time depends on varies between algorithms. For example, trial division is considered special purpose because the running time is roughly proportional to the size of the smallest factor.

- Trial division

- Wheel factorization

- Pollard's rho algorithm

- Algebraic-group factorisation algorithms, among which are Pollard's p − 1 algorithm, Williams' p + 1 algorithm, and Lenstra elliptic curve factorization

- Fermat's factorization method

- Euler's factorization method

- Special number field sieve

General-purpose

A general-purpose factoring algorithm's running time depends solely on the size of the integer to be factored. This is the type of algorithm used to factor RSA numbers. Most general-purpose factoring algorithms are based on the congruence of squares method.

- Dixon's algorithm

- Continued fraction factorization (CFRAC)

- Quadratic sieve

- General number field sieve

- Shanks' square forms factorization (SQUFOF)

Other notable algorithms

Heuristic running time

In number theory, there are many integer factoring algorithms that heuristically have expected running time

in o and L-notation. Some examples of those algorithms are the elliptic curve method and the quadratic sieve. Another such algorithm is the class group relations method proposed by Schnorr,[4] Seysen,[5] and Lenstra[6] that is proved under of the Generalized Riemann Hypothesis (GRH).

Rigorous running time

The Schnorr-Seysen-Lenstra probabilistic algorithm has been rigorously proven by Lenstra and Pomerance[7] to have expected running time ![L_n\left[1/2,1%2Bo(1)\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/71983caa9d1c402d557ec04bbd0b4e3f.png) by replacing the GRH assumption with the use of multipliers. The algorithm uses the class group of positive binary quadratic forms of discriminant Δ denoted by GΔ. GΔ is the set of triples of integers (a, b, c) in which those integers are relative prime.

by replacing the GRH assumption with the use of multipliers. The algorithm uses the class group of positive binary quadratic forms of discriminant Δ denoted by GΔ. GΔ is the set of triples of integers (a, b, c) in which those integers are relative prime.

Schnorr-Seysen-Lenstra Algorithm

Given is an integer n that will be factored, where n is an odd positive integer greater than a certain constant. In this factoring algorithm the discriminant Δ is chosen as a multiple of n, Δ= -dn, where d is some positive multiplier. The algorithm expects that for one d there exist enough smooth forms in GΔ. Lenstra and Pomerance show that the choice of d can be restricted to a small set to guarantee the smoothness result.

Denote by PΔ the set of all primes q with Kronecker symbol  . By constructing a set of generators of GΔ and prime forms fq of GΔ with q in PΔ a sequence of relations between the set of generators and fq are produced. The size of q can be bounded by

. By constructing a set of generators of GΔ and prime forms fq of GΔ with q in PΔ a sequence of relations between the set of generators and fq are produced. The size of q can be bounded by  for some constant

for some constant  .

.

The relation that will be used is a relation between the product of powers that is equal to the neutral element of GΔ. These relations will be used to construct a so-called ambiguous form of GΔ, which is an element of GΔ of order dividing 2. By calculating the corresponding factorization of Δ and by taking a gcd, this ambiguous form provides the complete prime factorization of n. This algorithm has these main steps:

Let n be the number to be factored.

- Let Δ be a negative integer with Δ = -dn, where d is a multiplier and Δ is the negative discriminant of some quadratic form.

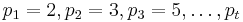

- Take the t first primes

, for some

, for some  .

. - Let

be a random prime form of GΔ with

be a random prime form of GΔ with  .

. - Find a generating set X of GΔ

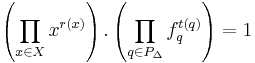

- Collect a sequence of relations between set X and {fq : q ∈ PΔ} satisfying:

- Construct an ambiguous form (a, b, c) that is an element f ∈ GΔ of order dividing 2 to obtain a coprime factorization of the largest odd divisor of Δ in which Δ = -4a.c or a(a - 4c) or (b - 2a).(b + 2a)

- If the ambiguous form provides a factorization of n then stop, otherwise find another ambiguous form until the factorization of n is found. In order to prevent useless ambiguous forms from generating, build up the 2-Sylow group S2(Δ) of G(Δ).

To obtain an algorithm for factoring any positive integer, it is necessary to add a few steps to this algorithm such as trial division, Jacobi sum test.

Expected running time

The algorithm as stated is a probabilistic algorithm as it makes random choices. Its expected running time is at most ![L_n\left[1/2,1%2Bo(1)\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/71983caa9d1c402d557ec04bbd0b4e3f.png) .[7]

.[7]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Kleinjung, et al (2010-02-18). Factorization of a 768-bit RSA modulus. International Association for Cryptologic Research. http://eprint.iacr.org/2010/006.pdf. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ LIEVEN M. K. VANDERSYPEN, et al (2007-12-27). NMR quantum computing: Realizing Shor's algorithm. Nature. http://www.nature.com/nature/links/011220/011220-2.html. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- ^ Lance Fortnow (2002-09-13). "Computational Complexity Blog: Complexity Class of the Week: Factoring". http://weblog.fortnow.com/2002/09/complexity-class-of-week-factoring.html.

- ^ Schnorr, Claus P. (1982). "Refined analysis and improvements on some factoring algorithms". Journal of Algorithms 3 (2): 101–127. doi:10.1016/0196-6774(82)90012-8.

- ^ Seysen, Martin (1987). "A probabilistic factorization algorithm with quadratic forms of negative discriminant". Mathematics of Computation 48 (178): 757–780. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1987-0878705-X.

- ^ Lenstra, Arjen K (1988). "Fast and rigorous factorization under the generalized Riemann hypothesis". Indagationes Mathematicae 50: 443–454.

- ^ a b H.W. Lenstra, and C. Pomerance; Pomerance, Carl (July 1992). "A Rigorous Time Bound for Factoring Integers" (PDF). Journal of the American Mathematical Society 5 (3): 483–516. doi:10.1090/S0894-0347-1992-1137100-0. http://www.ams.org/mcom/2006-75-256/S0025-5718-06-01870-9/S0025-5718-06-01870-9.pdf.

References

- Donald Knuth. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms, Third Edition. Addison-Wesley, 1997. ISBN 0-201-89684-2. Section 4.5.4: Factoring into Primes, pp. 379–417.

- Richard Crandall and Carl Pomerance (2001). Prime Numbers: A Computational Perspective (1st ed.). Springer. ISBN 0-387-94777-9. Chapter 5: Exponential Factoring Algorithms, pp. 191–226. Chapter 6: Subexponential Factoring Algorithms, pp. 227–284. Section 7.4: Elliptic curve method, pp. 301–313.

External links

- Video explaining uniqueness of prime factorization using a lock analogy.

- A collection of links to factoring programs

- Richard P. Brent, "Recent Progress and Prospects for Integer Factorisation Algorithms", Computing and Combinatorics", 2000, pp. 3-22. download

- Manindra Agrawal, Neeraj Kayal, Nitin Saxena, "PRIMES is in P." Annals of Mathematics 160(2): 781-793 (2004). August 2005 version PDF

- [1] is a public-domain integer factorization program for Windows. It claims to handle 80-digit numbers. See also the web site for this program MIRACL

- The RSA Challenge Numbers - a factoring challenge, no longer active.

- Eric W. Weisstein, “RSA-640 Factored” MathWorld Headline News, November 8, 2005

- Qsieve, a suite of programs for integer factorization. It contains several factorization methods like Elliptic Curve Method and MPQS.

- Source code by Paolo Ardoino, Three known algorithms and C source code.

- Factorization Source Code: by Paul Herman & Ami Fischman, C++ source code for many factorization algorithms including Pollard Rho & Shor's.

- a database containing factorizations, complete and incomplete, of over 80 million numbers.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![L_n\left[1/2,1%2Bo(1)\right]=e^{(1%2Bo(1))(\log n)^{\frac{1}{2}}(\log \log n)^{\frac{1}{2}}}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/344b6b22e7b4bfe04aeb505020a16453.png)